Ink tattoo

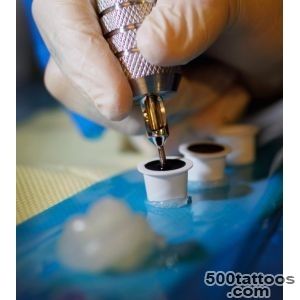

Although the scrubby workshops with unskilled workers and dubious safety precautions are largely a thing of the past, concern is growing among scientists about what happens inside tattooed skin. A new wave of research has revealed disturbing details about the chemicals in tattoo ink, including some endocrine disruptors and toxic metals, and a compound that has been identified as one of the most powerful skin carcinogens. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has launched studies on ink safety, but so far neither tattoo artists nor their customers seem particularly worried.

How popular are tattoos

More than 45 million Americans, including 36 percent of adults under 30, have at least one tattoo. Since tattoo shops have evolved from underground parlors into fashionable salons, ink has burst into mainstream culture. Despite well-known risks of infections, allergies, and scarring, the number of people getting tattooed continues to climb every year.

Chemical ingredients found in tattoo ink

A series of studies has found phthalates (phthalic acid esters), metals, and hydrocarbons that are potential carcinogens and endocrine disruptors inside commercially available tattoo inks. According to dermatologist Elizabeth Tanzi, co-director of the Institute of Dermatologic Laser Surgery in Washington, the ink introduced into the skin with small needles can cause allergic rashes, chronic skin reactions, infections, and inflammation from sun exposure. Research published in July confirmed that phthalates and other chemical ingredients likely contribute to these problems.

Cancer risks and benzopyrene

One of the chemicals found in black tattoo ink, benzopyrene, is a potent carcinogen that has caused cancer in animal tests. Dermatologists have published reports in medical journals describing rare cases where melanomas and other malignant tumors were detected in areas covered by tattoos. Whether these chemicals increase the risk of skin cancer in tattooed people remains an open question. "It is definitely possible and requires further research by the FDA," says Tanzi.

The FDA has begun a new study to examine the long-term safety of ink, including what happens when pigments are broken down in the body or interact with light. Research has shown that tattoo inks can migrate into a person's lymph nodes. While the long-term health effects, if any, remain unclear, the migration itself is a concern that scientists want to understand better.

Phthalates and heavy metals

In a study of 14 commercially available inks, scientists found low doses of dibutyl phthalate (DBP) in every sample tested. Dermatologists at the University of Regensburg in Germany wrote that the substances found in the ink may be partly responsible for adverse skin reactions to tattoos.

For phthalates, which can mimic estrogen or disrupt testosterone, the most concerning effects involve embryos and children. Prenatal exposure to DBP has been associated with feminization of the reproductive tract in boys. In adult men, phthalate exposure has been linked to sperm count defects and changes in thyroid hormones. Whether phthalates in tattoo inks carry the same level of risk is still uncertain, though experts do not recommend exposing pregnant or lactating women to them.

Colored inks often contain lead, cadmium, chromium, nickel, titanium, and other heavy metals that can trigger allergies and disease. Some pigments are industrial-grade colors described by the FDA as "suitable for printer ink or car paint."

PAHs in black ink

Black ink for tattoos, which is often made from soot, also contains products of combustion called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), as documented in a German study. PAHs include benzopyrene, one of the strongest known skin carcinogens. The study authors wrote: "Tattoo black ink entails administering a significant amount of phenol and PAH into the skin. Most of these PAHs are carcinogenic and can additionally form destructive atomic oxygen in the dermis when the skin is exposed to ultraviolet A radiation such as solar radiation." They reported that PAHs can remain in the skin for life and may influence skin integrity, potentially contributing to skin aging and cancer.

The tattoo-cancer debate

Scientists continue to debate the possible relationship between tattoos and cancer. Although cases of malignancies such as melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthomas have been described in tattoo areas over the past 40 years, it remains unclear what role tattoos play in their development. No large epidemiological study has been conducted, and designing one is difficult. Theoretically you could track a large group of tattooed people for health outcomes, but tattooing is still associated with other risk behaviors that could confuse the results, according to epidemiologist Geoffrey Kabat of the Medical College in the Bronx.

FDA regulation and oversight

The FDA has the authority to regulate tattoo inks under the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act, but the agency has never exercised full control, citing a lack of evidence of harm and other public health priorities. An FDA representative stated: "Because the dyes and inks used in tattoos have never been approved by the FDA, we do not know the specific composition. Consequently, we have not evaluated them for chronic diseases such as cancer."

Now the FDA is showing more curiosity and investing in research on ink ingredients. One key question is what happens to ink when a tattoo fades over time and under the influence of sunlight. Preliminary results show that Pigment Yellow 74, a common pigment in yellow tattoo inks, can be broken down by the body's enzymes. Under sunlight it also degrades into colorless components of unknown toxicity. When skin cells containing ink are destroyed by sunlight or laser radiation, the decomposition products can spread through the body.

What this means for tattoo clients

Previous studies have confirmed that tattoo ink migrates into human lymph nodes, but it is still unknown whether this migration has health consequences. The lack of FDA regulation has not slowed the tattoo industry, where experienced artists charge 125 to 200 dollars per hour. Artists build trusting relationships with loyal customers, and clients rarely ask about the long-term risks of ink ingredients. As one studio owner in San Francisco put it: "People come in concerned about how to get a good tattoo, not about health hazards."

Until more research clarifies the risks, the practical advice is straightforward: choose a reputable studio that uses inks from established manufacturers, ask your artist about the brands they use, avoid discount inks of unknown origin, and follow standard aftercare to minimize infection and irritation during healing.