Mafia tattoo

The relationship between organized crime and body marking stretches across centuries and continents, from Sicilian cosa nostra to Japanese yakuza to Russian vory v zakone. Understanding these visual codes from a historical and cultural perspective reveals how ink has been used as identification, hierarchy, and binding oath within closed criminal societies.

Origins of Criminal Identification Marks

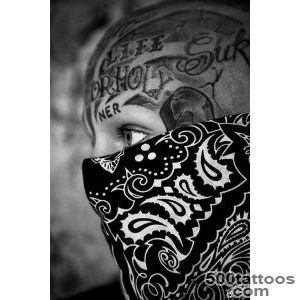

Long before modern law enforcement databases, criminal organizations needed ways to recognize members, communicate rank, and enforce loyalty. Permanent skin marks served all three purposes simultaneously. A specific image or placement could tell an insider everything they needed to know about the wearer's affiliation, role, and history without a single word being spoken. Wearing an unearned mark was considered a serious offense, sometimes punishable by death.

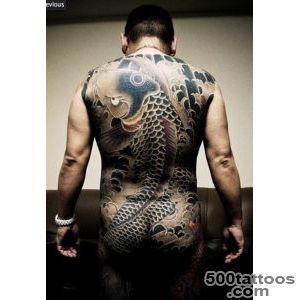

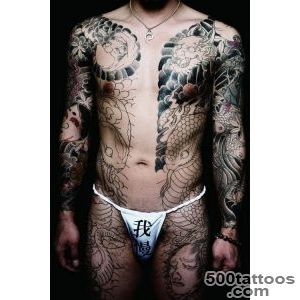

Yakuza Irezumi and Full-Body Coverage

Japanese organized crime groups developed one of the most elaborate marking traditions in the world. Full-body suits covering the torso, arms, and legs with mythological figures like dragons, tigers, koi, and Buddhist deities served as both identity and initiation ordeal. The extensive hand-poked process, called tebori, could take years to complete and demonstrated commitment, pain tolerance, and loyalty to the clan. Today, many Japanese public facilities still prohibit entry to people with large-scale traditional designs because of this association.

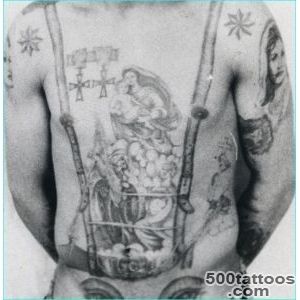

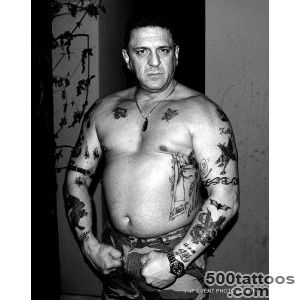

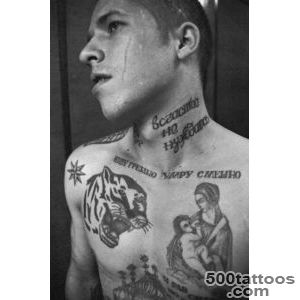

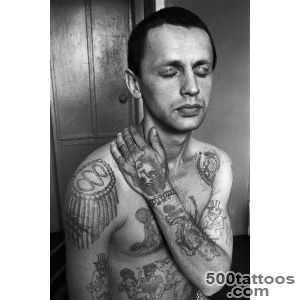

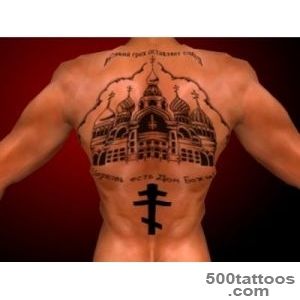

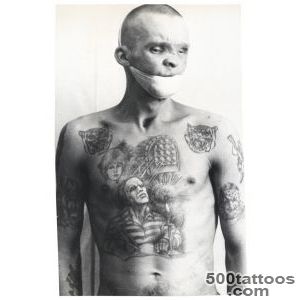

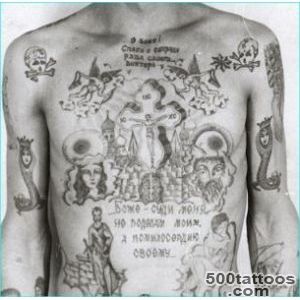

Russian Prison Hierarchy in Ink

The Soviet and post-Soviet prison system produced one of the most detailed criminal marking languages ever documented. Stars on the knees meant the wearer would kneel before no authority. Cathedrals with multiple domes indicated the number of sentences served. Specific animals, playing cards, and religious icons each carried precise meanings that fellow inmates could read instantly. Wearing a false mark resulted in forced removal, often by violent means.

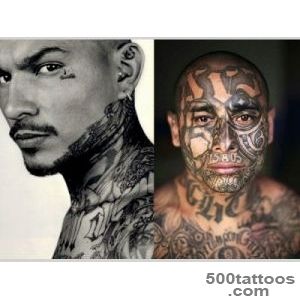

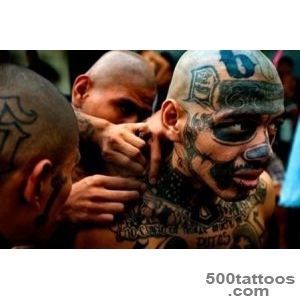

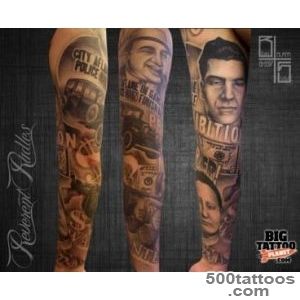

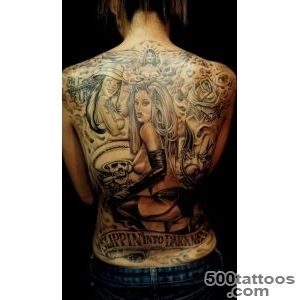

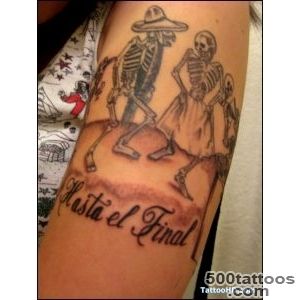

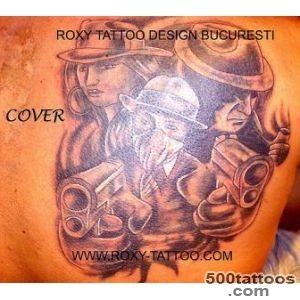

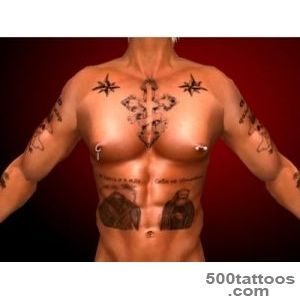

Latin American and Chicano Gang Symbols

Street and cartel organizations across Mexico, Central America, and the United States use numbers, letters, religious imagery, and territorial markers to indicate membership. The three dots on the hand, the number thirteen, and specific saints or skulls each communicate affiliation to those familiar with the code. These marks are often visible, functioning as both a warning and a declaration of belonging.

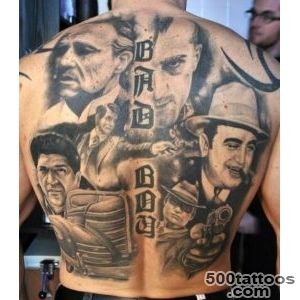

The Shift Toward Mainstream Awareness

Documentaries, films, and academic research have brought criminal marking traditions into wider public knowledge. This awareness has complicated the landscape: imagery that once belonged exclusively to criminal subcultures now appears in mainstream fashion and body art. Understanding the origin of a design is important because wearing certain marks without membership can still carry real-world consequences in some environments.

Historical and Educational Value

Studying these traditions is not an endorsement of criminal activity but a recognition that body marking has served complex social functions across all levels of society. The artistry, symbolism, and strict rule systems within criminal marking traditions reveal how humans use visual language to build identity, enforce belonging, and communicate status, themes that run through the entire history of skin art.