Maori tattoo

Maori body art, known as Ta Moko, is one of the oldest and most meaningful forms of permanent marking in the world. Unlike decorative ink chosen from a flash sheet, traditional Moko tells the story of a person's ancestry, social standing, and life achievements through a precise visual language of curves, spirals, and symmetry.

Sacred Origins and Cultural Significance

For the Maori people of Aotearoa New Zealand, Ta Moko is not decoration but identity. Each pattern is unique to the individual and encodes genealogy, tribal affiliation, and personal history. Historically, receiving Moko was a rite of passage that involved chiseling pigment into the skin with bone tools called uhi, a process far more painful and meaningful than modern needle work. The practice connects the physical body to whakapapa, the Maori concept of ancestral lineage.

Facial Moko and Its Meaning

The face is the most sacred canvas in Maori culture. A full facial Moko communicates rank, authority, and accomplishment, and no two are alike. The forehead area relates to social position, the cheeks to occupation, and the chin to mana, or prestige. Women traditionally received Moko on the chin and lips, called moko kauae, which signifies identity and connection to iwi, or tribal community.

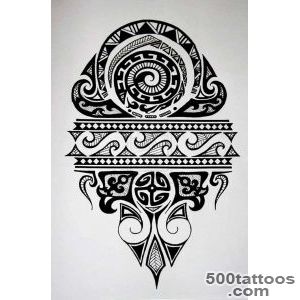

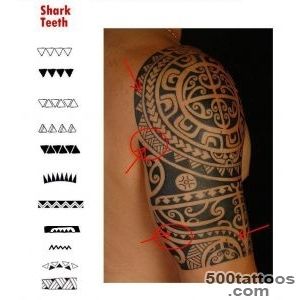

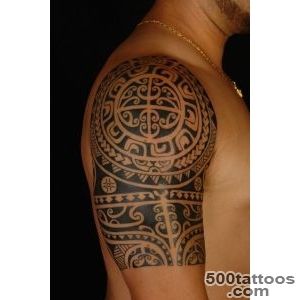

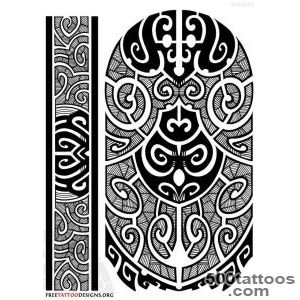

Spiral Patterns and Visual Language

The koru, a curling spiral inspired by an unfurling fern frond, represents new life, growth, and strength. Manawa lines are symmetrical patterns that reference the heart and breath, while pakati designs suggest bravery in battle. These elements combine into compositions that flow with the natural contours of the body, creating a visual map that is deeply personal and culturally specific.

Kirituhi and Respectful Adaptation

Kirituhi refers to Maori-inspired art created for people outside the culture. It uses similar visual elements but does not claim the genealogical authority of true Moko. If you are not Maori and want to honor this style, working with an artist who understands the distinction and can create original kirituhi is the respectful path. Copying someone else's Moko is considered deeply offensive.

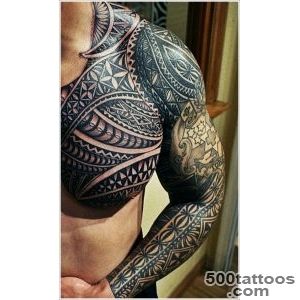

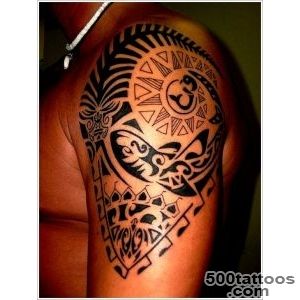

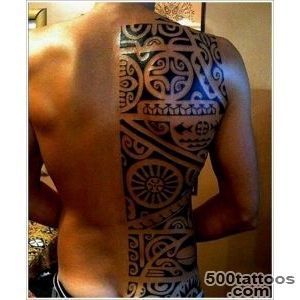

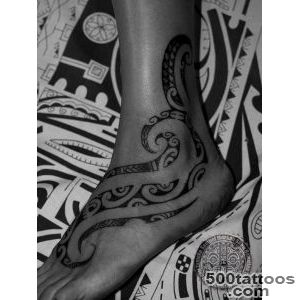

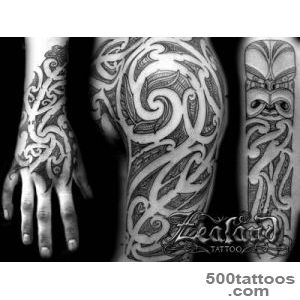

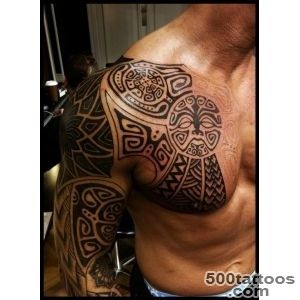

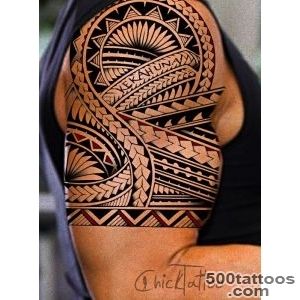

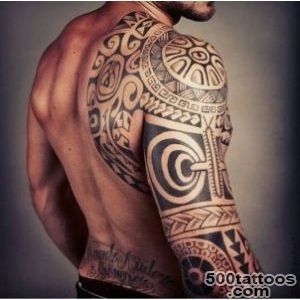

Placement and Modern Application

Shoulders, upper arms, calves, and thighs follow traditional placement zones where patterns can wrap around muscle groups naturally. Modern needle techniques replicate the visual density of traditional chiseling, and blackwork is the dominant color approach. Full-sleeve and half-sleeve compositions allow the flowing lines to move around the arm as a continuous design rather than a flat image.

Commitment and Cultural Awareness

Choosing this style means committing to understanding what the patterns represent, not just how they look. Research the history, respect the boundaries between Moko and kirituhi, and find an artist with genuine knowledge of Polynesian traditions. The result can be extraordinary when approached with the care and humility the art form deserves.